A few weeks ago I was looking at some of the performance metrics for my site. Specifically, I wanted to see how I was doing on our newest metric, first input delay (FID). My site is just a blog (and doesn’t run much JavaScript), so I expected to see pretty good results.

Input delay that’s less than 100 milliseconds is typically perceived as instant by users, so the performance goal we recommend (and the numbers I was hoping to see in my analytics) is FID < 100ms for 99% of page loads.

To my surprise, my site’s FID was 254ms at the 99th percentile. And while that’s not terrible, the perfectionist in me just couldn’t let that slide. I had to fix it!

To make a long story short, without removing any functionality from my site, I was able to get my FID under 100ms at the 99th percentile. But what I’m sure is more interesting to you readers is:

- How I approached diagnosing the problem.

- What specific strategies and techniques I used to fix it.

To that second point above, while I was trying to solve my issue I stumbled upon a pretty interesting performance strategy that I want to share (it’s the primary reason I’m writing this article).

I’m calling the strategy: idle until urgent.

My performance problem

First input delay (FID) is a metric that measures the time between when a user first interacts with your site (for a blog like mine, that’s most likely them clicking a link) and the time when the browser is able to respond to that interaction (make a request to load the next page).

The reason there might be a delay is if the browser’s main thread is busy doing something else (usually executing JavaScript code). So to diagnose a higher-than-expected FID, you should start by creating a performance trace of your site as it’s loading (with CPU and network throttling enabled) and look for individual tasks on the main thread that take a long time to execute. Then once you’ve identified those long tasks, you can try to break them up into smaller tasks.

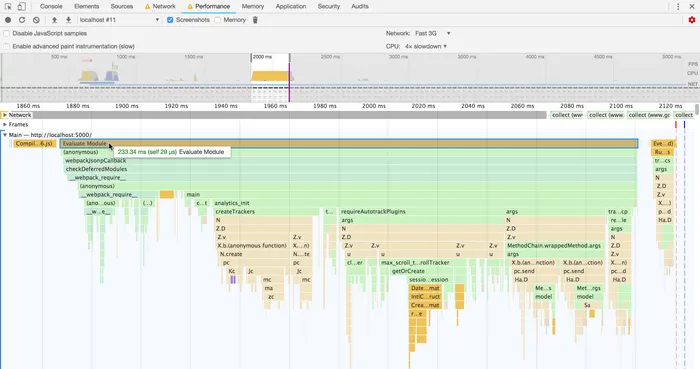

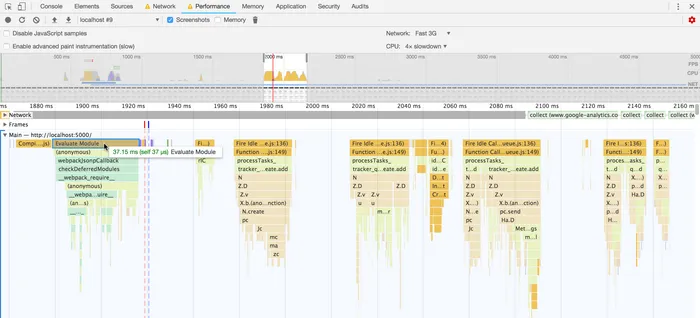

Here’s what I found when doing a performance trace of my site:

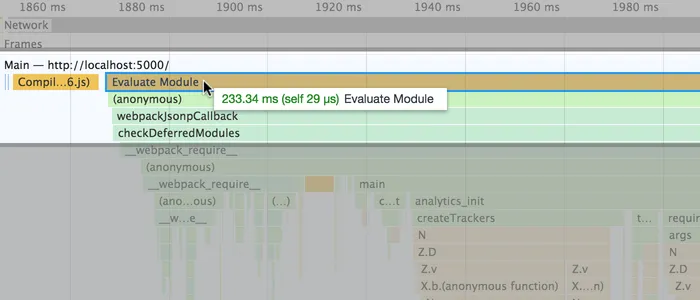

Notice, when the main script bundle is evaluated, it’s run as a single task that takes 233 milliseconds to complete.

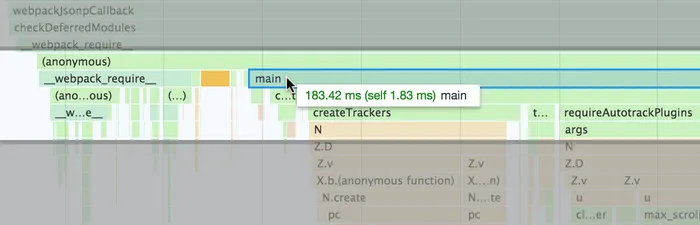

Some of this code is webpack boilerplate and babel polyfills, but the majority of it is from my script’s main() entry function, which itself takes 183ms to complete:

And it’s not like I’m doing anything ridiculous in my main() function. I’m initializing my UI components and then running my analytics:

const main = () => {

drawer.init();

contentLoader.init();

breakpoints.init();

alerts.init();

analytics.init();

};

main();

So what’s taking so long to run?

Well, if you look at the tails of this flame chart, you won’t see any single functions that are clearly taking up the bulk of the time. Most individual functions are run in less than 1ms, but when you add them all up, it’s taking more than 100ms to run them in a single, synchronous call stack.

This is the JavaScript equivalent of death by a thousand cuts.

Since the problem is all these functions are being run as part of a single task, the browser has to wait until this task finishes to respond to user interaction. So clearly the solution is to break up this code into multiple tasks, but that’s a lot easier said than done.

At first glance, it might seem like the obvious solution is to prioritize each of the components in my main() function (they’re actually already in priority order), initialize the highest priority components right away, and then defer other component initialization to a subsequent task.

While this may help some, it’s not a solution that everyone could implement, nor does it scale well to a really large site. Here’s why:

- Deferring UI component initialization only helps if the component isn’t yet rendered. If it’s already rendered than deferring initialization runs the risk that the user tries to interact with it and it’s not yet ready.

- In many cases all UI components are either equally important or they depend on each other, so they all need to be initialized at the same time.

- Sometimes individual components take long enough to initialize that they’ll block the main thread even if they’re run in their own tasks.

The reality is that initializing each component in its own task is usually not sufficient and oftentimes not even possible. What’s usually needed is breaking up tasks within each component being initialized.

Greedy components

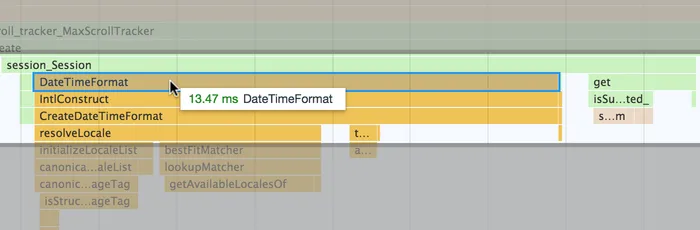

A perfect example of a component that really needs to have its initialization code broken up can be illustrated by zooming closer down into this performance trace. Mid-way through the main() function, you’ll see one of my components uses the Intl.DateTimeFormat API:

Creating this object took 13.47 milliseconds!

The thing is, the Intl.DateTimeFormat instance is created in the component’s constructor, but it’s not actually used until it’s needed by other components that reference it to format dates. However, this component doesn’t know when it’s going to be referenced, so it’s playing it safe and instantiating the Int.DateTimeFormat object right away.

But is this the right code evaluation strategy? And if not, what is?

Code evaluation strategies

When choosing an evaluation strategy for potentially expensive code, most developers select one of the following:

- Eager evaluation: where you run your expensive code right away.

- Lazy evaluation: where you wait until another part of your program needs the result of that expensive code, and you run it then.

These are probably the two most popular evaluation strategies, but after my experience refactoring my site, I now think these are probably your two worst options.

The downsides of eager evaluation

As the performance problem on my site illustrates pretty well, eager evaluation has the downside that, if a user tries to interact with your page while the code is evaluating, the browser must wait until the code is done evaluating to respond.

This is especially problematic if your page looks like it’s ready to respond to user input, but then it can’t. Users will perceive your page as sluggish or maybe even completely broken.

The more code you evaluate up front, the longer it will take for your page to become interactive.

The downsides of lazy evaluation

If it’s bad to run all your code right away, the next most obvious solution is to wait to run it until it’s actually needed. This way you don’t run code unnecessarily, especially if it’s never actually needed by the user.

Of course, the problem with waiting until the user needs the result of running that code is now you’re guaranteeing that your expensive code will block user input.

For some things (like loading additional content from the network), it makes sense to defer it until it’s requested by the user. But for most code you’re evaluating (e.g. reading from localStorage, processing large datasets, etc.) you definitely want it to happen before the user interaction that needs it.

Other options

The other evaluation strategies you can choose from all take an approach somewhere in between eager and lazy. I’m not sure if the following two strategies have official names, but I’m going to call them deferred evaluation and idle evaluation:

- Deferred evaluation: where you schedule your code to be run in a future task, using something like

setTimeout. - Idle evaluation: a type of deferred evaluation where you use an API like requestIdleCallback to schedule your code to run.

Both of these options are usually better than eager or lazy evaluation because they’re far less likely to lead to individual long tasks that block input. This is because, while browsers cannot interrupt any single task to respond to user input (doing so would very likely break sites), they can run a task in between a queue of scheduled tasks, and most browsers do when that task is caused by user input. This is known as input prioritization.

To put that another way: if you ensure all your code is run in short, distinct tasks (preferably less than 50ms), your code will never block user input.

Important! While browsers can run input callbacks ahead of queued tasks, they cannot run input callbacks ahead of queued microtasks. And since promises and async functions run as microtasks, converting your sync code to promise-based code will not prevent it from blocking user input!

If you’re not familiar with the difference between tasks and microtasks, I highly recommend watching my colleague Jake’s excellent talk on the event loop.

Given what I just said, I could refactor my main() function to use setTimeout() and requestIdleCallback() to break up my initialization code into separate tasks:

const main = () => {

setTimeout(() => drawer.init(), 0);

setTimeout(() => contentLoader.init(), 0);

setTimeout(() => breakpoints.init(), 0);

setTimeout(() => alerts.init(), 0);

requestIdleCallback(() => analytics.init());

};

main();

However, while this is better than before (many small tasks vs. one long task), as I explained above it’s likely still not good enough. For example, if I defer the initialization of my UI components (specifically contentLoader and drawer) they’ll be less likely to block user input, but they also run the risk of not being ready when the user tries to interact with them!

And while delaying my analytics with requestIdleCallback() is probably a good idea, any interactions I care about before the next idle period will be missed. And if there’s not an idle period before the user leaves the page, these callbacks may never run at all!

So if all evaluations strategies have downsides, which one should you pick?

Idle Until Urgent

After spending a lot of time thinking about this problem, I realized that the evaluation strategy I really wanted was one where my code would initially be deferred to idle periods but then run immediately as soon as it’s needed. In other words: idle-until-urgent.

Idle-until-urgent sidesteps most of the downsides I described in the previous section. In the worst case, it has the exact same performance characteristics as lazy evaluation, and in the best case it doesn’t block interactivity at all because execution happens during idle periods.

I should also mention that this strategy works both for single tasks (computing values idly) as well as multiple tasks (an ordered queue of tasks to be run idly). I’ll explain the single-task (idle value) variant first because it’s a bit easier to understand.

Idle values

I showed above that Int.DateTimeFormat objects can be pretty expensive to initialize, so if an instance isn’t needed right away, it’s better to initialize it during an idle period. Of course, as soon as it is needed, you want it to exist, so this is a perfect candidate for idle-until-urgent evaluation.

Consider the following simplified component example that we want to refactor to use this new strategy:

class MyComponent {

constructor() {

addEventListener('click', () => this.handleUserClick());

this.formatter = new Intl.DateTimeFormat('en-US', {

timeZone: 'America/Los_Angeles',

});

}

handleUserClick() {

console.log(this.formatter.format(new Date()));

}

}

Instances of MyComponent above do two things in their constructor:

- Add an event listener for user interactions.

- Create an

Intl.DateTimeFormatobject.

This component perfectly illustrates why you often need to split up tasks within an individual component (rather than just at the component level).

In this case it’s really important that the event listeners run right away, but it’s not important that the Intl.DateTimeFormat instance is created until it’s needed by the event handler. Of course we don’t want to create the Intl.DateTimeFormat object in the event handler because then its slowness will delay that event from running.

So here’s how we could update this code to use the idle-until-urgent strategy. Note, I’m making use of an IdleValue helper class, which I’ll explain next:

import {IdleValue} from './path/to/IdleValue.mjs';

class MyComponent {

constructor() {

addEventListener('click', () => this.handleUserClick());

this.formatter = new IdleValue(() => {

return new Intl.DateTimeFormat('en-US', {

timeZone: 'America/Los_Angeles',

});

});

}

handleUserClick() {

console.log(this.formatter.getValue().format(new Date()));

}

}

As you can see, this code doesn’t look much different from the previous version, but instead of assigning this.formatter to a new Intl.DateTimeFormat object, I’m assigning this.formatter to an IdleValue object, which I pass an initialization function.

The way this IdleValue class works is it schedules the initialization function to be run during the next idle period. If the idle period occurs before the IdleValue instance is referenced, then no blocking occurs and the value can be returned immediately when requested. But if, on the other hand, the value is referenced before the next idle period, then the scheduled idle callback is canceled and the initialization function is run immediately.

Here’s the gist of how the IdleValue class is implemented (note: I’ve also released this code as part of the idlize package, which includes all the helpers shown in this article):

export class IdleValue {

constructor(init) {

this._init = init;

this._value;

this._idleHandle = requestIdleCallback(() => {

this._value = this._init();

});

}

getValue() {

if (this._value === undefined) {

cancelIdleCallback(this._idleHandle);

this._value = this._init();

}

return this._value;

}

// ...

}

While including the IdleValue class in my example above didn’t require many changes, it did technically change the public API (this.formatter vs. this.formatter.getValue()).

If you’re in a situation where you want to use the IdleValue class but you can’t change your public API, you can use the IdleValue class with ES2015 getters:

class MyComponent {

constructor() {

addEventListener('click', () => this.handleUserClick());

this._formatter = new IdleValue(() => {

return new Intl.DateTimeFormat('en-US', {

timeZone: 'America/Los_Angeles',

});

});

}

get formatter() {

return this._formatter.getValue();

}

// ...

}

Or, if you don’t mind a little abstraction, you can use the defineIdleProperty() helper (which uses Object.defineProperty() under the hood):

import {defineIdleProperty} from './path/to/defineIdleProperty.mjs';

class MyComponent {

constructor() {

addEventListener('click', () => this.handleUserClick());

defineIdleProperty(this, 'formatter', () => {

return new Intl.DateTimeFormat('en-US', {

timeZone: 'America/Los_Angeles',

});

});

}

// ...

}

For individual property values that may be expensive to compute, there’s really no reason not to use this strategy, especially since you can employ it without changing your API!

While this example used the Intl.DateTimeFormat object, it’s also probably a good candidate for any of the following:

- Processing large sets of values.

- Getting a value from localStorage (or a cookie).

- Running

getComputedStyle(),getBoundingClientRect(), or any other API that may require recalculating style or layout on the main thread.

Idle task queues

The above technique works pretty well for individual properties whose values can be computed with a single function, but in some cases your logic doesn’t fit into a single function, or, even if it technically could, you’d still want to break it up into smaller functions because otherwise you’d risk blocking the main thread for too long.

In such cases what you really need is a queue where you can schedule multiple tasks (functions) to run when the browser has idle time. The queue will run tasks when it can, and it will pause execution of tasks when it needs to yield back to the browser (e.g. if the user is interacting).

To handle this, I built an IdleQueue class, and you can use it like this:

import {IdleQueue} from './path/to/IdleQueue.mjs';

const queue = new IdleQueue();

queue.pushTask(() => {

// Some expensive function that can run idly...

});

queue.pushTask(() => {

// Some other task that depends on the above

// expensive function having already run...

});

Note: breaking up your synchronous JavaScript code into separate tasks that can run asynchronously as part of a task queue is different from code splitting, which is about breaking up large JavaScript bundles into smaller files (and is also important for improving performance).

As with the idly-initialized property strategy shown above, idle tasks queues also have a way to run immediately in cases where the result of their execution is needed right away (the “urgent” case).

Again, this last bit is really important; not just because sometimes you need to compute something as soon as possible, but often you’re integrating with a third-party API that’s synchronous, so you need the ability to run your tasks synchronously as well if you want to be compatible.

In a perfect world, all JavaScript APIs would be non-blocking, asynchronous, and composed of small chunks of code that can yield at will back to the main thread. But in the real world, we often have no choice but to be synchronous due to a legacy codebase or integrations with third-party libraries we don’t control.

As I said before, this is one of the great strengths of the idle-until-urgent pattern. It can be easily applied to most programs without requiring a large-scale rewrite of the architecture.

Guaranteeing the urgent

I mentioned above that requestIdleCallback() doesn’t come with any guarantees that the callback will ever run. And when talking to developers about requestIdleCallback(), this is the primary explanation I hear for why they don’t use it. In many cases the possibility that code might not run is enough of a reason not to use it—to play it safe and keep their code synchronous (and therefore blocking).

A perfect example of this is analytics code. The problem with analytics code is there are many cases where it needs to run when the page is unloading (e.g. tracking outbound link clicks, etc.), and in such cases requestIdleCallback() is simply not an option because the callback would never run. And since analytics libraries don’t know when in the page lifecycle their users will call their APIs, they also tend to play it safe and run all their code synchronously (which is unfortunate since analytics code is definitely not critical to the user experience).

But with the idle-until-urgent pattern, there’s a simple solution to this. All we have to do is ensure the queue is run immediately whenever the page is in a state where it might soon be unloaded.

If you’re familiar with the advice I give in my recent article on the Page Lifecycle API, you’ll know that the last reliable callback developers have before a page gets terminated or discarded is the visibilitychange event (as the page’s visibilityState changes to hidden). And since in the hidden state the user cannot be interacting with the page, it’s a perfect time to run any queued idle tasks.

In fact, if you use the IdleQueue class, you can enable this ability with a simple configuration option passed to the constructor.

const queue = new IdleQueue({ensureTasksRun: true});

For tasks like rendering, there’s no need to ensure tasks run before the page unloads, but for tasks like saving user state and sending end-of-session analytics, you’ll likely want to set this option to true.

Note: listening for the visibilitychange event should be sufficient to ensure tasks run before the page is unloaded, but due to Safari bugs where the pagehide and visibilitychange events don’t always fire when users close a tab, you have to implement a small workaround just for Safari. This workaround is implemented for you in the IdleQueue class, but if you’re implementing this yourself, you’ll need to be aware of it.

Warning! Do not listen for the unload event as a way to run the queue before the page is unloaded. The unload event is not reliable and it can hurt performance in some cases. See my Page Lifecycle API article for more details.

Use cases for idle-until-urgent

Any time you have potentially-expensive code you need to run, you should try to break it up into smaller tasks. And if that code isn’t needed right away but may be needed at some point in the future, it’s a perfect use case for idle-until-urgent.

In your own code, the first thing I’d suggest to do is look at all your constructor functions, and if any of them run potentially-expensive operations, refactor them to use an IdleValue object instead.

For other bits of logic that are essential but not necessarily critical to immediate user interactions, consider adding that logic to an IdleQueue. Don’t worry, if at any time you need to run that code immediately, you can.

Two specific examples that are particularly amenable to this technique (and are relevant to a large percentage of websites out there) are persisting application state (e.g. with something like Redux) and analytics.

Note: these are all use cases where the intention is that tasks should run during idle periods, so it’s not a problem if they don’t run right away. If you need to handle high-priority tasks where the intention is they should run as soon as possible (yet still yielding to input), then requestIdleCallback() may not solve your problem.

Fortunately, some of my colleagues have proposals for new web platform APIs (shouldYield(), and a native Scheduling API) that should help.

Persisting application state

Consider a Redux app that stores application state in memory but also needs to store it in persistent storage (like localStorage) so it can be reloaded the next time the user visits the page.

Most Redux apps that store state in localStorage use a debounce technique roughly equivalent to this:

let debounceTimeout;

// Persist state changes to localStorage using a 1000ms debounce.

store.subscribe(() => {

// Clear pending writes since there are new changes to save.

clearTimeout(debounceTimeout);

// Schedule the save with a 1000ms timeout (debounce),

// so frequent changes aren't saved unnecessarily.

debounceTimeout = setTimeout(() => {

const jsonData = JSON.stringify(store.getState());

localStorage.setItem('redux-data', jsonData);

}, 1000);

});

While using a debounce technique is definitely better than nothing, it’s not a perfect solution. The problem is there’s no guarantee that when the debounced function does run, it won’t block the main thread at a time critical to the user.

It’s much better to schedule the localStorage write for an idle time. You can convert the above code from a debounce strategy to an idle-until-urgent strategy as follows:

const queue = new IdleQueue({ensureTasksRun: true});

// Persist state changes when the browser is idle, and

// only persist the most recent changes to avoid extra work.

store.subscribe(() => {

// Clear pending writes since there are new changes to save.

queue.clearPendingTasks();

// Schedule the save to run when idle.

queue.pushTask(() => {

const jsonData = JSON.stringify(store.getState());

localStorage.setItem('redux-data', jsonData);

});

});

And note that this strategy is definitely better than using debounce because it guarantees the state gets saved even if the user is navigating away from the page. With the debounce example, the write would likely fail in such a situation.

Analytics

Another perfect use case for idle-until-urgent is analytics code. Here’s an example of how you can use the IdleQueue class to schedule sending your analytics data in a way that ensures it will be sent even if the user closes the tab or navigates away before the next idle period.

const queue = new IdleQueue({ensureTasksRun: true});

const signupBtn = document.getElementById('signup');

signupBtn.addEventListener('click', () => {

// Instead of sending the event immediately, add it to the idle queue.

// The idle queue will ensure the event is sent even if the user

// closes the tab or navigates away.

queue.pushTask(() => {

ga('send', 'event', {

eventCategory: 'Signup Button',

eventAction: 'click',

});

});

});

In addition to ensuring the urgent, adding this task to the idle queue also ensures it won’t block any other code that’s needed to respond to the user’s click.

In fact, it’s generally a good idea to run all your analytics code idly, including your initialization code. And for libraries like analytics.js whose API is already effectively a queue, it’s easy to just add these commands to our IdleQueue instance.

For example, you can convert the last part of the default analytics.js installation snippet from this:

ga('create', 'UA-XXXXX-Y', 'auto');

ga('send', 'pageview');

Into this:

const queue = new IdleQueue({ensureTasksRun: true});

queue.pushTask(() => ga('create', 'UA-XXXXX-Y', 'auto'));

queue.pushTask(() => ga('send', 'pageview'));

(You could also just create a wrapper around the ga() function that automatically queues commands, which is what I did).

Browser support for requestIdleCallback

As of this writing, only Chrome and Firefox support requestIdleCallback(). And while a true polyfill isn’t really possible (only the browser can know when it’s idle), it’s quite easy to write a fallback to setTimeout (all the helper classes and methods mentioned here use this fallback).

And even in browsers that don’t support requestIdleCallback() natively, the fallback to setTimeout is definitely still better than not using this strategy because browsers can still do input prioritization ahead of tasks queued via setTimeout().

How much does this actually improve performance?

At the beginning of this article I mentioned I came up with this strategy as I was trying to improve my website’s FID value. I was trying to split up all the code that ran as soon as my main bundle was loaded, but I also needed to ensure my site continued to work with some third-party libraries that only have synchronous APIs (e.g. analytics.js).

The trace I showed before implementing idle-until-urgent had a single, 233ms task that contained all my initialization code. After implementing the techniques I described here, you can see I have multiple, much shorter tasks. In fact, the longest one is now only 37ms!

A really important point to emphasize here is that the same amount of work is being done as before, it’s just now spread out over multiple tasks and run during idle periods.

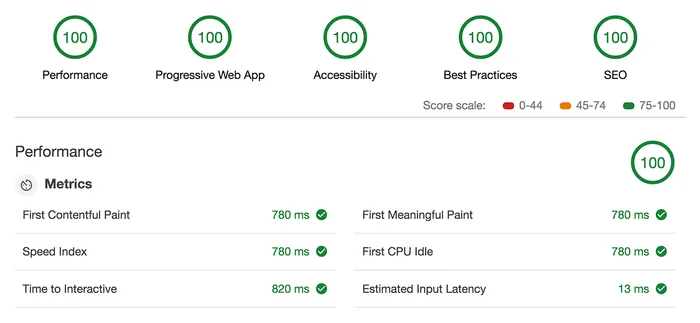

And since no single task is greater than 50ms, none of them affect my time to interactive (TTI), which is great for my lighthouse score:

Lastly, since the point of all this work was to improve my FID, after releasing these changes to production and looking at the results, I was thrilled to discover a 67% reduction in FID values at the 99th percentile!

| Code version | FID (p99) | FID (p95) | FID (p50) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before idle-until-urgent | 254ms | 20ms | 3ms |

| After idle-until-urgent | 85ms | 16ms | 3ms |

Conclusions

In a perfect world, none of our sites would ever block the main thread unnecessarily. We’d all be using web workers to do our non-UI work, and we’d have shouldYield() and a native Scheduling API) built into the browser.

But in our current world, we web developers often have no choice but to run non-UI code on the main thread, which leads to unresponsiveness and jank.

Hopefully this article has convinced you of the need to break up our long-running JavaScript tasks. And since idle-until-urgent can turn a synchronous-looking API into something that actually evaluates code in idle periods, it’s a great solution that works with the libraries we all know and use today.