Anyone who’s browsed the web on their phone has, at one point or another, experienced this situation:

You open a web page and click on something, but nothing happens.

You click on it again—still nothing happens.

You click on something else—nope, nothing.

This is bad enough on its own, but it often doesn’t end there. Here’s what usually happens next:

You start clicking everywhere just to get *some* feedback that your phone isn't broken—then suddenly a bunch of stuff all happens at the same time, and now you're on a completely different page and you have no idea how you got there.

If this sounds familiar, then you’ve experienced the opposite of interactivity on the web. But what exactly does the term “interactivity” mean?

I think most people reading this article probably know what the word “interactivity” means in general. The problem is, in recent years the word has been given a technical meaning (e.g. in the metric “Time to Interactive” or TTI), and unfortunately the specifics of that meaning are rarely explained.

So in this article I want to dig into the meaning of interactivity on the web. After all, I think it’s one of the most important things developers need to care about.

Interactivity on the web

For a page to be interactive, it has to be capable of responding quickly to user input. Whether a user is clicking a link, tapping on a custom component, or just scrolling through content, if the page can respond quickly (in a way that more or less feels “instant” to the user) then the page is interactive.

I think most developers generally understand this. What I don’t think most developers understand are the reasons why a page might not be interactive, and that’s a much bigger issue.

There are essentially just two reasons a page wouldn’t be able to respond quickly to user input (ignoring JS errors and other obvious bugs):

- The page hasn’t finished loading the JavaScript needed to control its DOM.

- The browser’s main thread is busy doing something else.

The first reason is important, but it’s been discussed a lot by folks in the community, and I don’t see much point in repeating it (this 5-minute video gives a great summary of the issue if you’re curious).

The second reason is complex and often overlooked, so that’s the primary thing I want to focus on here.

When the browser’s main thread is busy

While you often hear people say that browsers are multi-threaded (and this is true to some extent), the reality is a large portion of the tasks a browser will run need to happen on the same thread that handles user input (often called the “main thread” or the “UI thread”).

Without getting too deep into the weeds of browser internals (e.g. tasks, task queues, and the event loop[1]), the main point to understand is there are many cases where the browser has some code it wants to run (like an event listener in respond to a user’s click), but it can’t because it has to wait for other code to finish first. In this case the main thread is said to be “busy” or “blocked”.

Perhaps the best way to show this is with a demo. Take a look at this code, which runs a while loop continuously for 10 seconds.

function blockMainThreadUntil(time) {

while (performance.now() < time) {

// Do nothing...

}

}

blockMainThreadUntil(performance.now() + 10000);

While this code runs, nothing else can happen on the main thread. That means a user can’t:

- Click a link

- Select any text

- Check a checkbox

- Watch an animated GIF

- Type into an

<input>or<textarea>

Before showing the demo, I want to take a moment to emphasize just how bad this experience is. When the above code is running, it’s not just blocking other JavaScript code, it’s blocking all other tasks on the main thread, and that includes so-called native interactions you might not expect could be affected by user code.

In fact, even interactions like scrolling (which are usually handled on a separate thread) can sometimes be affected by a busy main thread (e.g. if a wheel, touchstart, or touchmove event listener has been added to the page).[2]

To see a blocked main thread in action, click the button below (which will add a wheel and touchstart event listener and run the while loop shown above), then try to select any text, click any link, or scroll around. Also, notice how the animated GIF stops animating:

Update: some browsers are now able to render animated GIFs while the main thread is blocked; however, that has not historically been the case, and not all browsers currently support this feature.

| Element | Example |

|---|---|

<img> | |

<a> | https://example.com |

<input> |

Warning! You might suddenly find yourself on a new page once the main thread is unblocked!

What blocks the main thread

You might be thinking: okay, but my code isn’t running a ten-second while loop; do I really need to worry about this?

Unfortunately the answer is still yes. It’s a lot easier for pages to block the main thread than you might initially think. In fact, merely loading JavaScript will block the main thread while the browser parses and compiles the code.[3]

My colleague Addy Osmani did a study of 6000+ websites built with popular web frameworks and found that on average they blocked the main thread for 4.4 seconds while just parsing and compiling JavaScript. That’s 4.4 seconds where users can’t click any links or select any text!

In addition to parsing and compiling, executing JavaScript also blocks the main thread. Every JavaScript function that runs on your page is going to block the main thread for some amount of time. While JavaScript functions tend to be small and usually execute very quickly, the more functions you run at a time, the more likely those are to add up to something noticeable by the user.

This is especially true if you use a web framework or virtual DOM library that manages component re-rendering in response to state changes. Many of these libraries define component lifecycle methods that all get run synchronously whenever there’s a change. For an app with a lot of components, this can easily be thousands of function calls.

An important point to understand is it’s not necessarily how much code you run that matters, it’s how you run it.

For example, if you have 1000 functions that each take 1ms to run and you run them sequentially in the same call stack, they will block the main thread for 1 second. But if you break up the execution of those functions into separate, asynchronous tasks (or where possible use requestIdleCallback), it may take longer but it won’t block the main thread. The browser will be able to interject in between calls and respond to user input.

A great example of this strategy is React’s recent architectural changes (a.k.a. fiber). To quote the React 16 release post:

Perhaps the most exciting area we’re working on is async rendering—a strategy for cooperatively scheduling rendering work by periodically yielding execution to the browser. The upshot is that, with async rendering, apps are more responsive because React avoids blocking the main thread.

Lastly, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention perhaps the biggest cause of non-interactivity on the web: third-party ads and widgets—which often run way too much code and frequently access properties of the main document, thus adding tasks to its main thread.

Third-party ads and widgets tend to be found on content sites rather than “app” sites, which brings up another important topic…

App sites vs. content sites

I hear a lot of people say things like: I run a content site, not an app, so I don’t really need to care about interactivity.

But this isn’t true! As I mentioned above, when you block the main thread you prevent users from clicking links or selecting text, and in the some cases you may even prevent scrolling! These are absolutely things that content sites need to care about.

How to tell if you have an interactivity problem

The tricky issue with interactivity is the same page may be interactive for one user (on a fast, desktop machine) but completely unresponsive for another (on a low-end phone). As developers, it’s important that we really grok this and actually measure interactivity on devices that reflect our users in the real world.

Earlier I said that for a page to be interactive it needs to be able to respond to user input quickly. Most current definitions of interactivity define “quickly” using the RAIL guidelines for responsiveness, which is within 100ms.

I also mentioned that the primary cause of unresponsiveness is tasks blocking the main thread. In order to reliably respond to user input within 100ms, it’s critical that no one single task runs for more than 50ms. This is because if input happens during a task, and the input listener itself (its own task) also takes time to run, then both of those tasks need to complete within 100ms for the interaction to feel instant to the user.

To account for this, tools and APIs that measure interactivity will only consider a page interactive if it runs no tasks longer than 50ms during a given period of time.

To determine if your own site is interactive, there are generally two approaches:

- Using tools or simulators (known as lab measurement).

- Getting data from actual users (known as real-user monitoring, or RUM).

And there are also two ways to think about interactivity and its effects:

- The probability of a user experiencing non-interactivity or unresponsive pages.

- A real user actually experiencing a non-interactive or unresponsive page while attempting to interacting with it.

This is similar to the philosophical tree falling in the forest problem: If a web page isn’t interactive, but the user doesn’t experience it, is it a problem?

My answer to this question is that it’s the experience of real users that ultimately matters. However lab measurements are invaluable tools in preventing bad user experiences from happening in the first place.

In other words, we should care about all of the above.

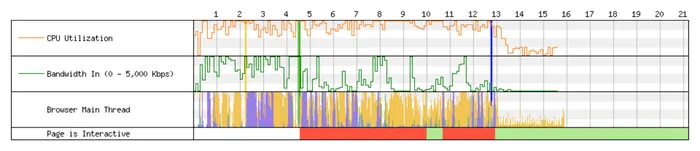

For lab testing, I highly recommend tools like Lighthouse, and WebPageTest, both of which measure TTI and also give additional interactivity information. For example, WebPageTest’s waterfall view has a “Page is Interactive” bar along the bottom. This is great for visualizing when these bad experiences would likely happen.

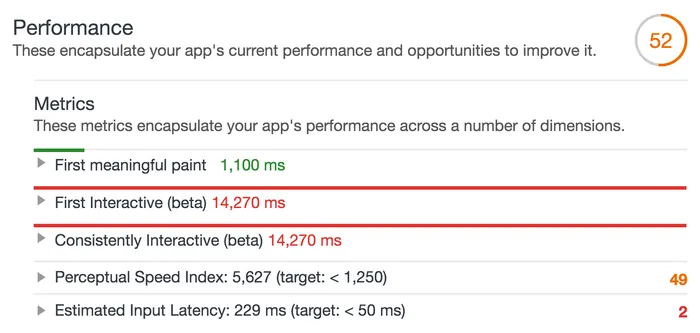

And Lighthouse gives you a score for your estimated input latency:

Note that this is “estimated input latency” because it’s a lab simulation; no users are actually interacting with this page so it’s a measure of probability.

If you want to measure actual input latency (RUM), you can use analytics tools like Google Analytics. For example, if your site has a menu toggle button, you might want to know any time it takes longer than 50ms for the event listener code to run (from the time the user clicked). The code to do that would look something like this:

const menuToggleBtn = document.querySelector('#menu-toggle');

menuToggleBtn.addEventListener('click', (event) => {

// Put your menu-toggle logic here...

// Then measure when it finished executing.

const latency = performance.now() - event.timeStamp;

// If it took more than 50ms, report it to Google Analytics.

if (latency > 50) {

// Assumes the availability of requestIdleCallback (or a shim).

requestIdleCallback(() => {

ga('send', 'event', {

eventCategory: 'Performance Metric'

eventAction: 'input-latency',

eventLabel: '#menu-toggle:click',

eventValue: Math.round(latency),

nonInteraction: true,

});

});

}

});

This code takes advantage of the fact that event.timeStamp reflects the time the operating system actually received the click, and performance.now() (when called inside the event listener) reflects the time the code actually ran.

While you could add code like this to every button on your site, I recommend starting with only the most critical UI components and going from there.

You can also measure general interactivity via RUM thanks to the new Long Tasks API, which, in conjunction with PerformanceObserver, can tell you anytime a single task blocks the main thread for more than 50ms. The code to track that using Google Analytics looks like this:

// Define a callback that sends Long Task data to Google Analytics.

function sendLongTaskDataToAnalytics(entryList) {

// Assumes the availability of requestIdleCallback (or a shim).

requestIdleCallback(() => {

for (const entry of entryList.getEntries()) {

ga('send', 'event', {

eventCategory: 'Performance Metrics',

eventAction: 'longtask',

eventValue: Math.round(entry.duration),

eventLabel: JSON.stringify(entry.attribution),

});

}

});

}

// Create a PerformanceObserver and start observing Long Tasks.

new PerformanceObserver(sendLongTaskDataToAnalytics).observe({

entryTypes: ['longtask'],

});

This information will let you know anytime the main thread isn’t fully interactive. It’ll also tell you which document frame (via the attribution property) was responsible for the long tasks, which can be really helpful in determining if third-party ads or widgets are contributing to bad user experiences on your site.

For more details on tracking user-experience metrics in code, check out my talk from last Google I/O. Also, for some general advice on how to properly track things with Google Analytics, you can refer to my article The Google Analytics Setup I Use on Every Site I Build.

Why does interactivity matter so much?

Recently, a group of researchers at Google working with the Coalition for better Ads ran an experiment to determine how much different types of ads annoy users. One type of “annoying” ad they tried would block the main thread for 10 seconds as soon as the ad was visible.

When the study was over and the results compiled, this 10-second blocking ad was found to be among the least annoying.

Confused as to why this would be the case, some researchers asked individual participants why they didn’t find it annoying that an ad was preventing them from interacting with the page.

The response they got was generally:

Oh, I didn’t realize it was the ad making the page slow. I just assumed it was the page since most web pages are slow on phones.

When I heard this story, it made me pretty sad, but it also highlighted just how big of a problem this is. Since we developers haven’t prioritized interactivity, our users have just come to expect the fact that things are going to be slow. What’s worse is even when the culprit is a third-party script, the site still gets blamed for it.

This means we developers need to hold third-parties accountable for their bad behavior. It’s our job since it affects our users’ experience and their opinion of our platform.

I hear a lot of web developers say things like “I want the web to win”, but the only way that’s going to happen is if we all prioritize user experience, especially on mobile devices. And the first step is actually investigating our sites to see if we have a problem.

What’s next

Hopefully you now have a better understanding of what interactivity means and why it matters. Next I strongly encourage you to measure the interactivity of your own sites on real devices and for real users. In my experience, developers are typically surprised by their results.

Finally, if you’re looking for ways to improve your interactivity metrics, Addy Osmani’s recommendations for lowering JavaScript startup cost is a great place to start. I also strongly second Alex’s Russell’s recommendation of implementing a performance budget.